The Unfolding Saga: AI, Academic Integrity, and the University Campus

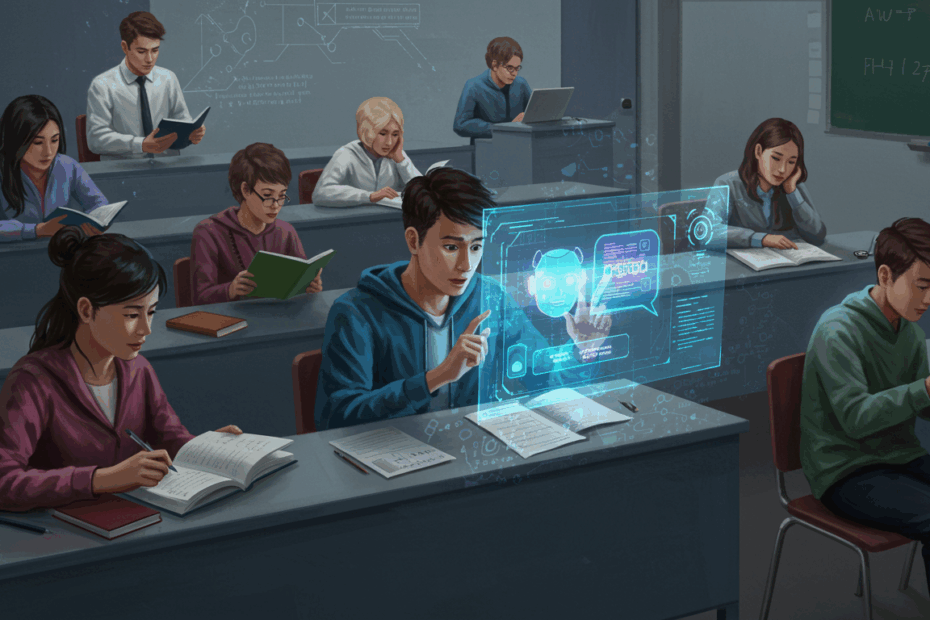

John: Welcome to our latest deep dive. Today, we’re tackling a subject that’s rapidly reshaping the academic landscape: the complex interplay between Artificial Intelligence, specifically generative AI like ChatGPT, and the age-old problem of cheating in universities. Recent reports, like those from The Guardian and Axios, paint a stark picture of a significant rise in students being caught using AI to complete their assignments. It’s more than just a new tool for academic dishonesty; it’s a fundamental challenge to how we assess learning and uphold integrity.

Lila: Thanks, John. It definitely sounds like a hot topic. When we say “AI cheating,” are we talking about something more sophisticated than just copying an answer from the internet? I’ve seen headlines mentioning “ChatGPT cheats,” and it sounds like a whole new level of problem for universities.

Basic Info: What Are We Talking About?

John: Precisely, Lila. This isn’t your grandfather’s plagiarism. “AI cheating” primarily refers to the misuse of generative AI tools – these are advanced software, like OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Google’s Gemini, that can create new content, including text, code, and even images, based on prompts they receive. Students might use these to generate entire essays, solve complex problems, or rephrase existing work to bypass traditional plagiarism detectors.

Lila: So, instead of a student struggling to write an essay, they can just type the essay question into one of these AI tools, and it spits out a completed paper? That sounds incredibly tempting, but also a bit terrifying from an educator’s perspective!

John: It is. These tools are powered by what we call Large Language Models, or LLMs (AI systems trained on colossal datasets of text and code). They don’t “understand” in a human sense, but they are exceptionally good at predicting the next word in a sequence, allowing them to generate coherent, often sophisticated, and human-like text. This makes it much harder to detect than simply finding a copied paragraph from Wikipedia.

Lila: And the news suggests universities are genuinely struggling with this. Are we seeing a dramatic increase in students getting caught? Because those Freedom of Information requests mentioned in The Guardian sound like they’ve uncovered some serious numbers.

Supply Details: The Scale of the Challenge

John: Indeed. The statistics are concerning. The Guardian’s investigation, which involved Freedom of Information (FOI) requests to numerous UK universities, revealed thousands of proven cases of academic misconduct involving AI. For instance, between 2023 and 2024, some reports indicated nearly 7,000 cases across the UK. And many experts, myself included, believe this is just the “tip of the iceberg.”

Lila: Wow, thousands! That’s a massive number. But you say “tip of the iceberg” – does that mean many more are getting away with it, or that universities aren’t equipped to catch everyone?

John: It’s likely a combination of both. Detection is a significant hurdle. While some universities are actively developing strategies and employing detection software, the AI tools themselves are constantly evolving, making it a cat-and-mouse game. Furthermore, as one of The Guardian articles highlighted, there’s a real concern about “universities that are *not* catching AI cheating.” Low numbers of reported cases at an institution don’t necessarily mean less cheating; it could indicate less effective detection or even a reluctance to address the problem head-on.

Lila: So, the figures we see are based on who gets *caught*. It makes you wonder about the true prevalence. If this is so widespread, what does it mean for the actual learning process and the value of a university degree? It feels like it could devalue the hard work of students who aren’t cheating.

John: That’s a critical concern, Lila, and one we’ll delve into. The integrity of academic qualifications is certainly at stake. If assignments can be outsourced to AI, it undermines the university’s ability to certify that a student has mastered the material and developed the necessary skills.

Technical Mechanism: How Students Are Using AI to Cheat (and How It Works)

John: Let’s look at how students are leveraging these tools. It’s not always a straightforward “write my essay” command, though that’s certainly a common use. Students might use AI for:

- Full Essay Generation: Providing a prompt and getting a complete draft or even a final paper.

- Sophisticated Paraphrasing: Inputting existing text (perhaps from multiple sources) and having the AI rewrite it in a “new” way to evade plagiarism checkers.

- Idea Generation and Outlining: Asking the AI to brainstorm arguments or create a structure for a paper, which, depending on university policy, might blur the lines of acceptable assistance.

- Coding Assignments: Generating functional code for programming tasks.

- Answering Specific Questions: Using it during take-home exams or for problem sets.

The underlying mechanism, as we touched on, involves LLMs. These models are trained by being fed vast quantities of text data. Through this training, they learn patterns, grammar, context, and even stylistic nuances. When you give it a prompt, the AI essentially predicts the most statistically probable sequence of words to follow, generating novel text that aligns with the input.

Lila: So, it’s like a super-advanced auto-complete, but for entire documents? Can professors actually tell if something was written by an AI? I imagine the early versions might have been clunky, but are they getting better?

John: They are improving at an astonishing rate. Early AI-generated text often had tell-tale signs: repetitive phrasing, lack of deep understanding, occasional factual “hallucinations” (where the AI confidently states incorrect information), or a very generic tone. However, models like GPT-4 and beyond are far more nuanced. They can adopt different writing styles, argue more coherently, and are generally harder to distinguish from human writing purely by reading them.

Lila: That leads to the obvious question: what about AI detection tools? Are they effective? It seems like if AI can write it, another AI should be able to detect it, right?

John: That’s the hope, and there are many AI detection tools on the market. These tools typically analyze text for characteristics common in AI-generated content, such as lower “perplexity” (predictability of word choice) or “burstiness” (variations in sentence length and complexity). However, it’s an ongoing arms race. AI-generated text can be tweaked (sometimes by another AI, or by the student) to bypass detectors. Furthermore, these detectors are not infallible; they can produce false positives (flagging human work as AI) and false negatives (missing AI-generated work). OpenAI even discontinued its own AI classifier tool due to its low rate of accuracy, which speaks volumes about the difficulty.

Lila: So, no silver bullet on the detection front yet. That really puts universities in a tough spot. They can’t just rely on software to solve this for them.

The Human Element: Why Are Students Turning to AI?

John: Exactly. And it’s important to understand the “why” behind this trend. It’s not always a case of malicious intent or laziness, though those factors can play a part. Students are under immense pressure: academic workload, the drive for high grades, extracurricular commitments, and sometimes, a feeling that certain assignments are just “busy work” with little real-world relevance.

Lila: That’s a really interesting point. I saw an article on Vox suggesting some students might not even perceive using AI as “cheating” in the traditional sense, especially if they’re just using it to get past writer’s block, generate an outline, or polish their grammar. Where do we draw the line between a helpful tool and academic dishonesty?

John: That’s the million-dollar question, and it’s forcing a re-evaluation of what we consider academic integrity in the age of AI. Professor Tim Wilson discussed this as needing a “new classroom contract.” The lines are indeed blurry. Is using AI to brainstorm ideas cheating? What about using it to draft an introduction that the student then heavily edits? Or to check for grammatical errors, much like Grammarly, but on a more advanced scale? University policies are scrambling to catch up and define these boundaries.

Lila: So, for some students, it might genuinely feel like they’re just using a very advanced calculator or spell-checker. If the end product reflects their understanding after they’ve interacted with the AI, is that always a problem? Or is the issue more when they wholesale submit AI-generated work as their own original thought?

John: The latter is unequivocally cheating under almost any academic policy. The former – using AI as an assistant – is where the grey areas emerge. The core principle of academic work is that it should reflect the student’s own learning, critical thinking, and effort. If AI is doing the heavy lifting of thinking and composing, that principle is violated. However, if it’s used as a tool to augment human capability, much like a researcher uses a database, then the conversation becomes more nuanced and depends heavily on transparency and the specific rules set by the institution or instructor.

Team & Community: Who’s Involved in This AI-Cheating Ecosystem?

John: This isn’t just a student-professor issue; it’s a whole ecosystem. You have:

- Students: As we’ve discussed, they are the primary users, with motivations ranging from outright cheating to seeking assistance or coping with pressure.

- Universities and Educators: They are on the front lines, responsible for upholding academic standards, adapting teaching methods, formulating policies, and dealing with instances of misconduct. This involves everyone from individual lecturers to entire administrative departments.

- AI Developers (like OpenAI, Google, Anthropic): These are the creators of the powerful generative AI tools. Interestingly, companies like OpenAI are now also trying to position themselves as partners in education, offering their tools to institutions, as seen with the Cal State system deal mentioned by the New York Times.

- AI Detection Tool Developers: A growing industry aiming to provide solutions for identifying AI-generated content, though as we’ve noted, with mixed success.

- Academic Integrity Officers and Bodies: Specialists within universities who investigate misconduct cases and help shape policy.

- Employers and Society at Large: Ultimately, they rely on the integrity of academic qualifications.

Lila: It’s quite a paradox for companies like OpenAI, isn’t it? They unleash these incredibly powerful tools, see them being used for cheating, and then come back to universities offering partnerships or solutions. How are universities navigating that relationship?

John: With a mixture of caution and curiosity. On one hand, there’s undeniable concern about the disruption AI has caused. On the other, many educators and institutions recognize that AI is here to stay and possesses enormous potential as an educational tool if used correctly. OpenAI, for its part, argues that its mission is to ensure AI benefits all of humanity, and that includes education. They are promoting responsible AI use and exploring features like watermarking or educational licenses. But the initial shockwave has definitely forced universities to be reactive.

Lila: And what about the academic community itself? Are professors and departments sharing effective strategies for dealing with AI, or is it more of an individual battle for each educator trying to figure things out in their own classroom?

John: There’s a growing movement towards sharing best practices. Academic conferences, journals, and inter-university collaborations are increasingly focusing on AI’s impact. Organizations like the International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI) are providing resources and fostering discussion. However, the pace of AI development is so rapid that it’s a constant challenge to disseminate effective, up-to-date strategies across the board. Some institutions are certainly more proactive and better resourced than others in this regard.

Use-Cases & Future Outlook: Adapting Education in the Age of AI

John: Given that AI isn’t going away, the focus is shifting from pure prevention to adaptation and integration. Universities are exploring a multifaceted approach:

- Revising Academic Integrity Policies: Clearly defining what constitutes acceptable and unacceptable use of AI tools for coursework. This is a foundational step, and as Baylor University’s guide shows, some are still in the process.

- Transforming Assessment Methods: This is crucial. There’s a significant move towards assessments that are harder to outsource to AI. This includes more in-class, supervised exams; oral examinations (viva voces); presentations; practical, project-based learning; and, yes, even a return to handwritten essays and “blue book” exams in some cases, as reported by Inside Higher Ed and Axios.

- Educating Students on Ethical AI Use: Rather than outright bans, many are opting to teach students about the capabilities and limitations of AI, and how to use it responsibly and ethically as a tool, with proper attribution.

- Exploring AI as a Legitimate Teaching and Learning Aid: This is the proactive side. AI can potentially offer personalized tutoring, assist with research by summarizing papers or finding sources, help students practice concepts, or provide feedback on early drafts (when disclosed and permitted).

Lila: So, it’s not just about catching cheats, but fundamentally changing *how* students are taught and tested? The idea of going back to handwritten essays and blue books feels almost archaic in our digital world, but I can see why it’s happening. It’s harder to get an AI to handwrite an essay in a supervised exam room!

John: Precisely. It’s about ensuring authenticity in assessment. If an assignment can be completed entirely by current AI, it might not be assessing the skills we intend it to – like critical thinking, original argumentation, or in-depth understanding. The shift is towards tasks that require higher-order cognitive skills, application of knowledge in novel contexts, or direct demonstration of understanding in real-time. It’s forcing educators to ask: what skills are truly essential, and how can we best measure them in this new environment?

Lila: You mentioned AI as a teaching aid. That’s a more optimistic angle. How could that work in practice without just becoming another way for students to take shortcuts?

John: The key is transparency and integration into the learning process. For example, an AI could act as a Socratic tutor, asking a student questions to guide them through a problem rather than just giving the answer. It could provide instant feedback on the structure or clarity of a draft, prompting the student to think more deeply. Or it could help students navigate vast amounts of information for research, identifying relevant papers, though the critical analysis must still be human. The New York Times piece on OpenAI partnering with Cal State to embed AI in “every facet of college” points to this broader ambition of AI as an integral part of the educational ecosystem, not just an external threat.

Different Institutional Approaches

John: As you might expect with such a disruptive technology, there isn’t a one-size-fits-all response from universities. We’re seeing a spectrum of approaches. Some institutions, or individual departments, initially reacted with near-total bans on AI tools for any graded work. Others have been more permissive, trying to establish guidelines for ethical use from the outset.

Lila: That must be so confusing for students, especially if they’re taking courses across different departments with conflicting rules, or if they transfer schools! One professor might say “AI is strictly forbidden,” while another encourages its use for brainstorming.

John: It is, and this inconsistency is a major challenge. We’re seeing:

- Proactive Institutions: These universities are developing comprehensive, campus-wide AI policies, investing in faculty training, and redesigning curricula to incorporate AI literacy and ethical usage. They often have dedicated task forces looking at the issue.

- Reactive Institutions: These might be slower to formalize policies, often leaving it to individual instructors to decide, which can lead to the inconsistencies you mentioned. They might be playing catch-up as incidents of AI misuse rise.

- Varied Detection Investment: Some universities invest heavily in AI detection software and training, while others may lack the resources or be skeptical of the current technology’s reliability. This contributes to the disparity in reported cheating cases – the Times Union article noting “local colleges say AI cheating isn’t rampant” could reflect genuinely lower rates, or less robust detection compared to national trends.

- Focus on Education vs. Punishment: Some prioritize educating students about AI ethics, while others may take a more punitive stance from the get-go. Most are trying to find a balance.

Lila: And what about the AI tools themselves? Is there a difference between, say, using an AI for grammar checking versus one that writes whole paragraphs? Are universities trying to differentiate between types of AI assistance?

John: Yes, that differentiation is critical, but also difficult to codify. Most universities have long accepted tools like spell checkers or grammar assistants (e.g., Grammarly). The new generative AI tools go far beyond that by creating original content. Policies often try to distinguish between AI as a ‘tool’ (like a calculator or search engine, used to *assist* human thought) and AI as an ‘agent’ (doing the thinking or writing *for* the human). The problem is, the most advanced AI tools can blur this line, acting as both. Clear guidelines often revolve around the degree of intellectual contribution: if the core ideas, structure, and expression are not the student’s own, it’s problematic.

Risks & Cautions: The Perils of Unchecked AI Use in Academia

John: The stakes are incredibly high if AI misuse becomes normalized or goes unchecked. We’re looking at several significant risks:

- Devaluation of Degrees: If qualifications can be obtained with minimal genuine effort or learning, their value in the eyes of employers and society diminishes.

- Erosion of Critical Skills: The process of researching, drafting, and refining arguments is how students develop critical thinking, analytical abilities, and effective communication skills. Over-reliance on AI can stunt this development.

- Equity and Access Issues: Not all students have equal access to the most sophisticated (often paid) AI tools or the knowledge to use them effectively and discreetly. This could create a new digital divide.

- Authenticity Crisis in Assessment: If educators cannot reliably determine whose work they are assessing, the entire assessment system is compromised.

- The “Output” Trap: Education might become focused on merely producing an output (an essay, a solution) rather than on the process of learning and understanding.

- Impact on Student Honesty: Constant temptation and seeing peers potentially get away with AI misuse can erode the ethical compass of students who would otherwise not cheat.

Lila: That point about eroding critical skills is really worrying. If students aren’t going through the struggle of writing and thinking for themselves, what are they actually learning? Are we risking a future where graduates know how to prompt an AI but can’t formulate an original argument on their own?

John: That’s the core fear expressed by many educators. The “struggle” is often where the deepest learning occurs. If AI consistently provides an easy way out, those essential cognitive muscles may not develop. It forces a re-examination of the very purpose of higher education – is it merely content delivery and credentialing, or is it about fostering intellectual growth, creativity, and problem-solving abilities? The answer to that question will heavily influence how institutions respond to AI.

Lila: And what about the students who choose *not* to use AI inappropriately? Are they put at a disadvantage if their peers are using it to get better grades or finish assignments faster? That seems incredibly unfair.

John: It’s a major fairness and equity concern. Honest students might feel pressured to also use AI to keep up, or become demoralized seeing others seemingly benefit from academic dishonesty. This creates a toxic academic environment. Moreover, it raises questions about what “effort” means. If one student spends 20 hours crafting an essay and another generates a comparable one in 20 minutes with AI, the grading system faces a severe challenge in rewarding genuine intellectual labor.

Expert Opinions / Analyses: What the Pundits Are Saying

John: The discourse among academics, technologists, and commentators is rich and varied, but a few key themes emerge. As highlighted by Axios, there’s a real fear that AI could be “wrecking America’s educational system” if not handled correctly. This isn’t just hyperbole; it reflects deep concern about the foundational aspects of learning and assessment.

Lila: “Wrecking the system” is strong language! Are there any more optimistic takes, or is the general consensus quite dire?

John: There are certainly concerned voices. The eWeek article citing an expert who called the detected cheating “the tip of the iceberg” underscores the scale of the hidden problem. However, many experts also see this as an inflection point, a catalyst for necessary change. The idea of a “new classroom contract,” as mentioned in the YouTube video by Professor Tim Wilson, suggests a move towards re-establishing expectations and responsibilities for both students and educators in an AI-suffused world. It’s less about turning back the clock and more about navigating a new reality.

Lila: So, it’s not just alarm bells, but also calls for adaptation? What kind of adaptations are being most seriously discussed by these experts?

John: Many advocate for a multi-pronged approach. First, a fundamental rethinking of assessment – moving away from tasks easily completed by AI towards those that require unique human skills like creativity, critical analysis of complex novel situations, and in-person demonstration of knowledge. Second, there’s a push for AI literacy, teaching students not just *how* to use these tools, but how to use them *ethically and critically*. Third, some, like in the WSJ Op-Ed referenced by TaxProf Blog, suggest more radical changes like eliminating online classes or banning screens in classrooms for certain activities to ensure authenticity, though these are more contentious. The overarching theme is that AI necessitates a more personal, engaged, and robust approach to education and assessment, one that AI cannot easily replicate.

Lila: It sounds like experts believe this is a moment for education to evolve significantly, perhaps even for the better in the long run, if it can successfully navigate these challenges. But that’s a big ‘if’.

John: A very big ‘if’. There’s also the perspective, like the one from Vox where a professor noted “My students think it’s fine to cheat with AI. Maybe they’re right…”, which challenges the traditional utilitarian view of humanities education. If assignments are perceived as mere hoops to jump through, students may feel more justified in using tools to clear them efficiently. This points to a deeper need to demonstrate the value and relevance of academic tasks themselves.

Latest News & Roadmap: The Evolving Landscape

John: This field is anything but static; it’s evolving weekly. Key recent developments include:

- Ongoing Data Releases: The Guardian and other outlets continue to publish findings from Freedom of Information requests, keeping the scale of AI cheating in the public eye and pressuring universities to respond. The “thousands of UK students caught” (Cybernews) is a recurring headline.

- Policy Updates: Universities worldwide are in a continuous cycle of reviewing and updating their academic integrity policies for each new academic year, trying to keep pace with AI advancements.

- Strategic AI Partnerships: We’re seeing more formal collaborations, like OpenAI’s initiative to embed its technology with the California State University system, affecting hundreds of thousands of students. This signals a move from AI as a shadow tool to an officially integrated one.

- The Detection Dilemma: The debate around the efficacy and ethics of AI detection tools continues. There’s no foolproof solution yet, and concerns about false positives and the “surveillance” feel of some tools persist.

- Shift in Pedagogy: Anecdotal and published evidence shows more educators actively changing their assignment types and assessment methods – more presentations, in-class work, and unique project prompts.

Lila: So, students heading to university next year, or even those currently enrolled, should expect more explicit rules about AI, and possibly different kinds of assignments than they’ve seen before?

John: Absolutely. They should proactively seek out their institution’s AI policy, and even specific course policies, as they can vary. They should also be prepared for assessments that may require more direct demonstration of their individual understanding and skills, potentially in supervised settings. The key thing to watch over the next 12-18 months will be how these new strategies play out: do they curb AI misuse? Do they genuinely enhance learning? And how will AI tools themselves evolve to perhaps offer more transparent, ethical assistance, or conversely, become even better at evading detection?

Lila: It really does feel like a “reckoning,” as The Guardian put it. Universities are being forced to confront some very fundamental questions about what they do and how they do it. It’s a massive challenge, but also maybe an opportunity to innovate.

John: Precisely. A crisis often serves as a catalyst for innovation. The challenge is immense, but it’s also pushing higher education to innovate in pedagogy, assessment, and its engagement with technology. The goal isn’t to fight technology, but to harness it and adapt to it in a way that preserves and even enhances the core mission of education: fostering genuine human learning and intellectual development.

FAQ: Your Questions Answered

Lila: Let’s tackle some common questions people might have. John, first up: Is using ChatGPT for my university essay always considered cheating?

John: Generally, if you submit work generated by ChatGPT (or any AI) as your own original work, yes, that is almost universally considered cheating and a violation of academic integrity policies. However, some instructors or institutions *might* permit its use for specific, clearly defined purposes, like brainstorming or checking grammar, *if explicitly stated and properly attributed*. The golden rule is: always check your institution’s and your specific course’s policy. When in doubt, ask your professor before using any AI tool for graded assignments.

Lila: Okay, that makes sense. Next: How can universities detect AI-written text? Is it foolproof?

John: Universities use a combination of methods. Some employ AI detection software, which analyzes text for patterns suggestive of AI generation (like consistency, perplexity, or lack of personal voice). Professors also rely on their experience – they often know their students’ writing styles and can spot inconsistencies or text that lacks depth or critical engagement. However, no current detection method is foolproof. Detection software can have false positives or negatives, and AI-generated text can be edited to appear more human. It’s an ongoing challenge.

Lila: Good to know it’s not a perfect science. What are the consequences of getting caught using AI inappropriately for academic work?

John: Consequences can be severe and vary by institution but typically range from a failing grade on the assignment or the course, to suspension, or even expulsion for repeated or serious offenses. It can also be noted on a student’s academic record, potentially impacting future educational or career prospects. Universities take academic integrity very seriously.

Lila: Definitely not worth the risk then! Here’s one a lot of students might wonder: Can AI be a helpful study tool without it being ‘cheating’?

John: Yes, absolutely. AI can be a powerful study aid if used ethically and transparently. For example, you could use an AI to:

- Explain complex concepts in simpler terms.

- Generate practice questions on a topic.

- Help you brainstorm ideas for a project (before you start writing).

- Get feedback on the clarity or grammar of a draft you’ve already written yourself (if permitted).

- Summarize long research papers to help you quickly grasp the main points (though you must still read and cite the original).

The key is that the AI is *assisting* your learning process, not doing the learning or the work *for* you. Again, always be clear on your institution’s guidelines.

Lila: That’s a helpful distinction. A big-picture question now: Will AI make university degrees worthless?

John: This is a major concern, but the answer is likely no, provided universities adapt successfully. If institutions can evolve their teaching and assessment methods to ensure graduates genuinely possess the skills and knowledge their degrees claim, then degrees will retain their value. AI challenges universities to be better at fostering and certifying uniquely human skills like critical thinking, creativity, complex problem-solving, and ethical judgment. If they rise to this challenge, degrees could even become *more* valuable as indicators of these AI-resistant skills.

Lila: And finally, John, we’ve seen mentions of “blue books” making a comeback. What are ‘blue books’ and why are they suddenly relevant again in the age of AI?

John: “Blue books” are simply lined examination booklets, common in US universities, used for handwritten, in-class essays and exams. They’re becoming relevant again because handwritten, supervised exams are very difficult to cheat on using current AI. Students write their answers in a controlled environment, without access to internet-connected devices. It’s a low-tech solution to a high-tech problem, aiming to ensure the work produced is genuinely the student’s own, done in real-time.

Related Links & Further Reading

John: For those looking to delve deeper, we recommend exploring some of the sources that have informed our discussion:

- Reports from The Guardian on AI cheating in UK universities.

- Articles from EdScoop and Axios on the rise of AI in education and its challenges.

- Inside Higher Ed for analyses on faculty responses and shifts in curriculum.

- University-specific academic integrity guidelines (many are available online, like Baylor University’s developing guide).

- Publications from organizations like the International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI).

Lila: It’s clear this is a rapidly evolving story, John. The intersection of AI and academic integrity is going to keep us, and universities, busy for a long time to come.

John: Indeed, Lila. The key will be fostering a culture of integrity, adapting educational practices, and embracing AI as a tool for learning, not a shortcut to bypass it. Thanks for the insightful questions.

The views expressed in this article are for informational purposes only and do not constitute academic advice. Always consult your institution’s specific academic integrity policies. Do Your Own Research (DYOR) on how to ethically use any technological tool in your studies.